by Una Sinnott

A ceremony in Trinity College Dublin yesterday marked the first step in returning 13 skulls to Inishbofin more than 130 years after they were stolen from the island by visiting anthropologists.

The remains of islanders, believed to be hundreds of years old, were taken in 1890 by British anthropologist Alfred Haddon and his assistant Andrew Dixon, and have been stored at the Old Anatomy Museum in Trinity every since.

The remains were laid in a traditional Inishbofin coffin, made by islander Christopher Day, at yesterday’s ceremony before being brought by hearse to Athenry. They will return to the island on Saturday.

A funeral Mass will be held on the island on Sunday, followed by a burial of the skulls at St Colman’s Monastery, close to where they had once rested, exactly 133 years to the day since they were removed.

This week’s events mark the culmination of a decade-long campaign by islanders and others to have the remains returned to their rightful home.

The campaign was spearheaded by Marie Coyne, who runs the Inishbofin Heritage Museum and has written about the graveyard at St Colman’s, and anthropologist Dr Ciarán Walsh.

The past two years in particular have seen the campaign grow apace, with petitions, letters and meetings between the islanders and Trinity’s Colonial Legacies Review Working Group. The group agreed earlier this year to faciltate the return of the skulls to Inishbofin, a landmark move which is likely to see similar requests for the return of other Colonial-era remains, including a further 11 skulls in the same collection, one of which was taken from Inis Mór.

Marie Coyne expressed her relief yesterday that the remains were finally returning home.

“Even though it’s a sad occasion, it’s a funeral I’ll be glad to go to,” she said. “They were stolen. They didn’t ask to be in a cupboard in a corridor for 133 years. They were in their surroundings with their relatives in their graveyard and it was plundered. They were taken out of it, so it’s only right that they go back.”

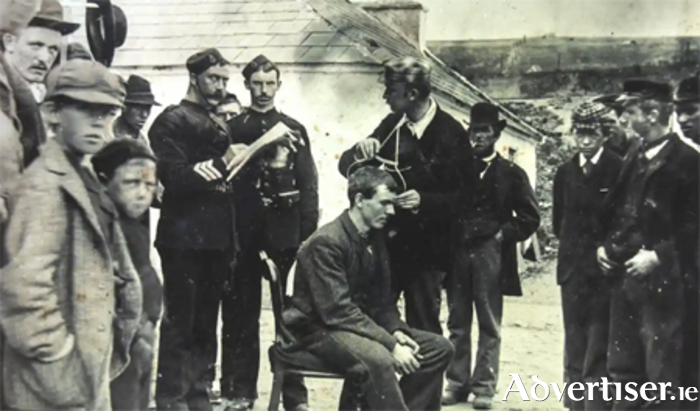

Haddon and Dixon visited Inishbofin in 1890 while undertaking a fishing survey of islands along the western seaboard and, while there, found a number of skulls which had been left in a corner of St Colman’s Monastery, a common practice with human remains which had been accidentally disinterred while digging new graves. The pair returned after dark to collect several of the skulls and remove them from the island.

“When the coast was clear we put our spoils in the sack and cautiously made our way back to the road,” Haddon later wrote in his diary. “The sailors wanted to take the sack when we got back to the boat, but Dixon would not give it up and when asked what was in it said ‘Potheen’ [sic].

“We got the skulls aboard and then we packed them in Dixon’s Portmanteau and locked it and no except our two selves had an idea that there are a dozen human skulls on board and they shan’t know either.”

According to Dr Ciarán Walsh, who became involved in the campaign through his work on a biography of Alfren Haddon, the acquisition of the skulls allowed Haddon to begin practising as an anthropologist.

“When he got back to Dublin he was very struck that Inis Meáin islanders were different from Inis Oírr, and from Inis Mór, and all of them were different from their cousins on the mainland in Connemara, so he got the idea that you could find the original pre-colonial population of Ireland in isolated communities in the west of Ireland, and one way to differentiate them was to measure their skulls,” he explained. “He set up a laboratory in Trinity in 1891, and a year later they started measuring skulls in the Aran Islands.”

The Inishbofin remains, along with one skull taken from Teampall Bhreacáin in Aran’s Seven Churches, and 10 taken from St Finian’s Bay in Co Kerry, formed the Haddon-Dixon Collection in Trinity and were used as evidence for his now long-discredited theory.

While the future of the skulls from Co Kerry and Aran have yet to be determined, it is hoped that this week’s repatriation of the Inishbofin remains will see the other communities facilitated in bringing home the other skulls in the Haddon-Dixon Collection.

“The whole anthropological world was watching Inishbofin today,” Dr Walsh added. “We had a ceremony in Trinity, it was a very moving ceremony. It sort of dawned on us how big this was, and how much public support we had.

“Today wasn’t about beating Trinity, it was about, in the bright sunshine in the square of TCD, Marie Coyne was vindicated in her 10 year search to have the rights of her community met.”