Search Results for 'West Bridge'

16 results found.

Councillors renew calls for speed controls in Loughrea

Concerns about speeding and traffic safety once again dominated the Loughrea Municipal District meeting on Monday, September 8.

The Galway and Salthill Tramway Company

The mid-19th century was an era of little movement of people for social or pleasure purposes. In the post-Famine era, it was only business people of necessity, those who were emigrating or those whose financial circumstances allowed who travelled. Railway travel had come Galway in 1851 and there were a few horse drawn omnibuses operating between the city and the village of Salthill, which was really a rural backwater. But, it was becoming a fashionable place to live and was developing as a tourist destination. It was therefore no surprise when a tramway system between the city and the village was proposed.

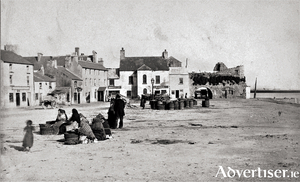

The Fishmarket

The village of Claddagh was a unique collection of thatched cottages arranged in a very random fashion, a place apart, occupied by a few thousand souls. They had their own customs, spoke mainly in Irish, intermarried, elected their own king and had a code of laws unique to the village. Virtually the entire male population was involved in fishing, but when they landed their catch, the women took over and they were the ones who went out and sold the product.

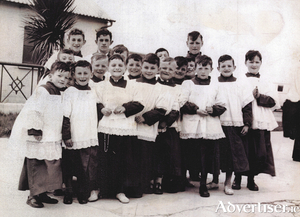

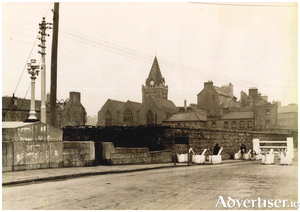

Saint Patrick’s Church

This photograph of St Patrick’s Church and part of Forster Street was taken from the Galway/Clifden Railway Line overlooking James Mahon’s Field where the circuses used to be long ago. It was taken c1920.

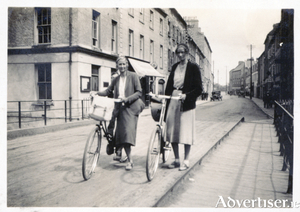

George Chambers’ photographic archive

George Chambers was born in England in 1873. He lived at Temple Fortune Lane in Middlesex. He travelled extensively and this included several trips to Ireland. In 1929, he toured parts of West Cork and Wicklow; in 1931, he visited Galway city and the Aran Islands and on subsequent trips he went to the Blasket Islands, to Achill and Clare Islands, and to various other islands off the coast of Donegal.

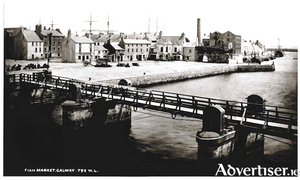

Wolfe Tone Bridge

Wolfe Tone Bridge was the third bridge to be built over the river. The West Bridge (now known as O’Brien’s Bridge) was the first and dates from medieval times. The Salmon Weir Bridge dates from 1820, and the Wolfe Tone Bridge was built in the mid-19th century.

O’Brien’s Bridge

The Parliamentary Gazetteer of Ireland was published in 1845 and stated that, “The old, or west bridge, over the main current of the Galway River, was built in 1342; and till the erection of the new bridge [the Salmon Weir Bridge, built 1819] was the only passage from the eastern districts of the county to the great peninsulated district of Iar-Connaught. In 1558, a gate and tower were erected at its west end; and afterwards, another gate and tower were erected in its centre; but these were long ago entirely demolished. About 42 years ago, the bridge was thoroughly repaired on its north side, and was pronounced by architects to be strong; but it soon experienced the effects of the neglect which are so generally apparent in the town; and in consequence of dilapidated parapets, narrow carriage-way and the utter want of side-pavements and of lights, it was, a few years ago, a rather hazardous means of crossing a deep and impetuous river on a dark night.”

The West Bridge, a brief history of the early years

The city of Galway was known in ancient times as ‘Streamstown’ because the Galway River divided into several small waterways in addition to the main river. The river was much more spread out then and was fordable in some places. The city was placed on the east side of the river, which acted as protection against the Irish families displaced by the Norman settlers who took over the area in the early 13th century. The walls of the city provided protection on the east and north side of the city and the various gates allowed access. The river was a barrier to trade with Iar-Chonnacht and so the merchant families began to feel the need to build a bridge to help expand trade, it would provide access to customers from the west, and also allow them to bring in their produce, fruit, vegetables, meat, hay, etc, to the various markets in town.

The Fishmarket

The village of the Claddagh was a unique collection of thatched houses arranged in a very random fashion, occupied by a few thousand souls. They had their own customs, spoke mainly in Irish, intermarried each other, had their own code of laws, and elected their own king. He was quite powerful in many respects and usually solved local disputes. Claddagh people rarely went outside the village to courts of justice. Virtually the entire male population was involved in fishing, but when they landed their catch, it was the women who took over. They were the members of the family who went out and sold the product.

Balls Bridge, 1685

This drawing is of a detail from “A Prospect of Galway” drawn by Thomas Phillips in 1685. It shows the southern end of the middle suburb with Balls Bridge on the left, and the bit of an arch you can see on the far right was part of the West Bridge. Balls Bridge is the bridge over what is now the canal between Upper and Lower Dominick Street, and the buildings we are looking at would be the backs of Lower Dominick Street as seen roughly from across the road from where the Fisheries Tower is today. The West Bridge is where O’Brien’s Bridge is today.