Search Results for 'James Hack Tuke'

5 results found.

The Galway General Omnibus Company

Our photograph today shows a Karrier double-decker bus which was operated by the Galway General Omnibus Company. It was taken at the Spring Show in the RDS in 1924, before it went into revenue earning service. The side panel carries the name of the company, but not the crest. The small lettering on the chassis below the word ‘Galway’ reads ’12 m.p.h.’ A major problem with this type of vehicle was its chain drive which frequently slipped off and caused breakdowns. The bus had solid-tyred wheels and was uncomfortable to ride in.

Was James Hack Tuke the Oskar Shindler of his day?

A surprising rescuer of the Tuke assisted emigration scheme from the west of Ireland came from the London government. After the first group of 1,315 people had sailed from Galway for America on April 28 1882, the Tukes’ emigration fund was practically exhausted. Yet the demand for places grew each day. Now more than 6,000 applications, mainly from the Clifden area, but also from Belmullet, Newport and Oughterard, poured into the Clifden union where James Hack Tuke had his office. While poverty and famine remained endemic in the west of Ireland, people with spirit must have felt that the day-to-day grind was never ending. The threat of another Great Famine was very real. They wanted a new life.

James Hack Tuke and his plan to assist emigration from west of Ireland

The agricultural crisis of 1879, and growing civic unrest, prompted the Society of Friends in England to send James Hack Tuke to the west to inquire into conditions and to distribute relief. Tuke, the son of a well-to-do tea and coffee merchant family in York, England, published his observations in Irish Distress and its Remedies: A visit to Donegal and Connaught in the spring of 1880. In clear-cut language he highlighted the widespread distress and destitution at a time when the British government questioned the extent of the crisis.

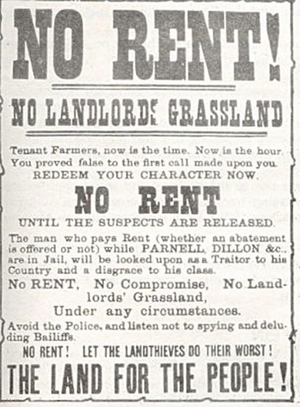

The gathering storm

The threat of another famine in 1879, within living memory of the horror and catastrophe of the Great Famine some 29 years earlier, brought renewed terror to the vulnerable tenant farmers in the west of Ireland. This time it was not just the humble potato, but severe weather conditions which devastated crops and feed stuffs over a three year period. Farm incomes dropped dramatically, landlords fussed that rents would not be paid. Whereas some landlords were patient, others warned that evictions would follow if rents were not paid on time.

Hundreds of thousands starved while the sea teemed with fish

Reading William Henry’s book Famine - Galway’s Darkest Days*, I was struck yet again by the fact that while thousands of people died of starvation in the west of Ireland, when whole communities abandoned their homes in a desperate search for food, our seas were boiling with fish. The author tells us that in Galway at the beginning of the Great Famine in 1845 the Claddagh fishermen fiercely protected their fishing rights in the Bay, which they regarded as their exclusive property. But as the famine dragged on to the end of the decade the Claddagh fishermen had no means left for catching fish. They had pawned their boats and fishing equipment for food. The historian Cecil Woodham-Smith in her classic account of the Great Famine**, tells us that on January 9 1847, ‘all boats were drawn up to the quay wall, stripped to the bare poles, not a sign of tackle or sail remaining....not a fish was to be had in the town, not a boat was at sea.’