Search Results for 'Harbour Commissioners'

8 results found.

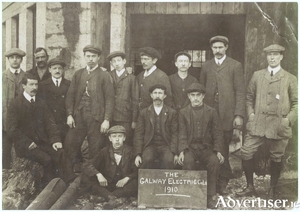

The Galway Electric Light Company

The Galway Electric Light Company was set up by James Perry, an engineer and County Surveyor of the Western District of Galway, and his brother, Professor John Perry, to generate electricity. On November 1, 1888, they applied for permission from the Galway Town Commissioners to ‘erect poles in some parts of the town as an experiment for the electric lighting of the town’. The company had established a generating station at Newtownsmith in an old flour mill which had existed since the 1600s and straddled the Friar’s River. They installed a hydroelectric turbine in the watercourse which was linked to a generator producing alternating current.

Dredging the Docks, 1963

Since Galway Docks were first constructed, they have undergone many changes. In the decade before the last world war, when transalantic liners were regular callers at the port, and when a fairly thriving coastal trade was being carried out, plans were prepared for the port so that Galway might cater more efficiently for sea traffic. There was a major scheme to build the Dún Aengus dock, the new pier, and to deepen the channel from 1937 to 1939. This meant the removal of thousands of tons of mud, soft materials, and granite. Most of this material was dumped near Hare Island. The work took longer than it should, mostly because of industrial disputes, but it was finally completed in 1939. Two units of the contractor’s equipment, a rock breaker and a floating crane, lay in the Commercial Dock throughout the war years.

Did a midsummer murder silence a guilty pilot?

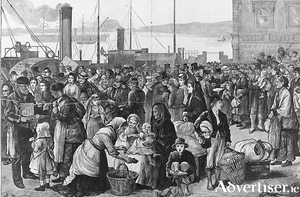

In June 1858 Galway town was in a fever of wild speculation and excitement. Its vision for a magnificent transatlantic port off Furbo, reaching deep into Galway Bay, where passengers from Britain, and throughout the island of Ireland, would be brought to their emigration ship in the comfort of a train, now faced being scuppered by the apparent criminal intent of the two local pilots.

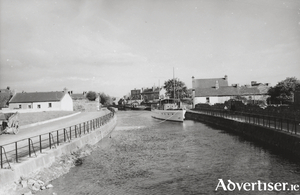

The last boat to use the canal

On March 8, 1848, work was started on the Eglinton Canal. The Harbour Commissioners had been anxious to develop the New Dock. There were about 300 boats in the Claddagh and the amount of seaweed landed for manure in the spring of 1845 was 5,000 boat loads, averaging three tons each. The seaweed factory had been moved up to ‘The Iodine’, so the work on the canal was vital. It would allow boats to go from the Claddagh Basin up to the lake, boats from Cong and Maam to get to the sea, and improve the mill-power on the Galway River.

The ‘blue moonlight’ of Galway 1893

Our Swedish journalist Hugo Vallentin arrived in Galway in the late summer of 1893. He had spent the previous weeks travelling through Dublin, Cork, Killarney and Limerick, assessing people’s reactions to the progress of Gladstone’s Second Home Rule act, which he believed was a question of interest to the whole ‘civilised world’.

The ‘blue moonlight’ of Galway 1893

Our Swedish journalist Hugo Vallentin arrived in Galway in the late summer of 1893. He had spent the previous weeks travelling through Dublin, Cork, Killarney and Limerick, assessing people’s reactions to the progress of Gladstone’s Second Home Rule act, which he believed was a question of interest to the whole ‘civilised world’.

Lindbergh

Out of the mists of the Monday afternoon of October 23 1933, there came to Galway a seaplane with a blue black fuselage, orange wings, and silver floats. She circled low over The Claddagh, swooped across the old Spanish Arch, and taking a wide sweep over Lough Corrib, swung around and landed near the lighthouse at 65 miles an hour with scarcely a ripple on the water. Claddagh boats put out in welcome, for it was Colonel Charles A Lindbergh who had flown alone from New York to Paris in May 1927, in 33.5 hours. He had come to Galway as a technical adviser of Pan-American Airways to see what facilities Galway Harbour had to offer as a seaplane base. The Claddagh boatmen towed his plane into New Docks where he was met by several local dignitaries.

Did a midsummer murder silence a guilty pilot?

In June 1858 Galway town was in a fever of excitement. Its vision for a magnificent transatlantic port off Furbo, reaching deep into in Galway Bay, where passangers from Britain, and throughout the island of Ireland, would be brought to their emigration ship in the comfort of a train, could now be scuppered by the apparent carelessness of the two local pilots.