Search Results for 'Edward Nangle'

5 results found.

‘Rather than die, the people submitted’

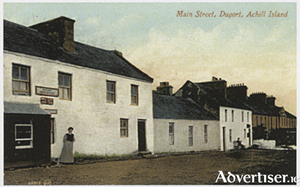

The Great Famine of 1845 - 49 hit Achill Island particularly hard. Given the poor quality of its soil there was little or no alternative to the potato crop which failed throughout those years. Once the severity of the calamity became apparent, and that help from the government was begrudging and insufficient, there was a sensible coming together of Protestant and Catholic clergy to try to calm and feed the people.

Six boys and the Achill Mission

In the summer of 1840 two of London’s most prolific writers and journalists, Mr and Mrs S C Hall, set out from London for an ambitious tour of Ireland. They would later publish their journey and observations in Ireland - its Scenery and Character, a best selling three volume snap-shot of Ireland, sumptuously illustrated by engravings created by the best artists of its time*. It is a treasured collector’s item today.

Victims of a sectarian war

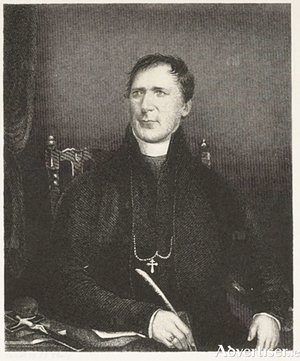

Even though it was in the furthermost parish of Archbishop MacHale’s large Tuam archdiocese, once he realised the permanency and the extent of the Protestant settlement on Achill Island (built and directed by the fervent Rev Edward Nangle in the 1830s),* the archbishop was consumed with fury. He waged a belated but rather terrifying campaign to have it scorned and ignored by the island’s 6,000 residents.

‘There is no place outside Hell, that enrages the Almighty more…’

A sort of panic obsessed the Archbishop of Tuam, John MacHale, when he realised the extent of the foothold gained by the uncompromising Church of Ireland evangelist Edward Nangle. Achill Island after all, was the very backyard of his immense diocese.

The Protestant enclave of Inishbiggle

In the 1650s, Catholics were uprooted from their productive, arable, lands in several Irish counties by Oliver Cromwell’s Protestant army and forced at musket point to desolate, barren, Connacht. Their confiscated lands, the better holdings in Ireland, were distributed to Protestant settlers, Cromwell’s army as pay, and carved up to pay debts. Maps of Ireland, pre and post Cromwell, detailing the regression of the predominantly Catholic associated Irish language and customs point to a culture that was deliberately and officially forced to areas thought of as being so inhospitable they would not survive. County Mayo was included among these religious and cultural ghettoes. The living standards of the banished Catholics fell dangerously low and remained so for centuries. Christian duty led some within the Protestant clergy to later establish evangelical missions in the wild Irish west to give relief to the descendants of those very same Catholics. Salvation and, dishonourably, food were offered through conversion to Protestantism. Whereas 17th century Protestants believed it was God's will that godless Catholics be sent to suffer and perhaps perish in Mayo, 19th century Protestants believed it was His will that these (still godless) Catholics be reclaimed so that they might be saved. The Rev Edward Nangle's Achill Island Mission set out to do just that in 1831.